Architecture of Munich, Bavaria, Germany

Home to the famous Oktoberfest, Munich is the capital of Bavaria and one of Germany’s architectural highlights. The city was a key component in the medieval Duchy of Bavaria and has roots dating back to the Romanesque and Gothic Ages. Munich also prospered throughout the Renaissance and Baroque periods and would eventually become the capital of the independent Kingdom of Bavaria in 1806. Munich is filled with countless buildings from every major architectural age, and whether you visit for the beer or the buildings, Munich will leave you wanting more of that quintessential Bavarian Culture.

Map of Munich

Map of Munich highlighting some of the city’s main attractions.

1. Marienplatz & New Town Hall

2. Frauenkirche

3. Residenz

4. Maximilianstraße

Table of Contents

Use these buttons to navigate to different sections of the article

History of Munich

The Rebuilding of Munich

Many of Munich’s most important buildings were completely devasted in the Allied Bombing Raids of WWII. The left image above shows a view of the Munich Residenz, which was particularly hard-hit. The right image shows lion statues that have fallen from the top of Munich’s Triumphal Arch, the Siegestor.

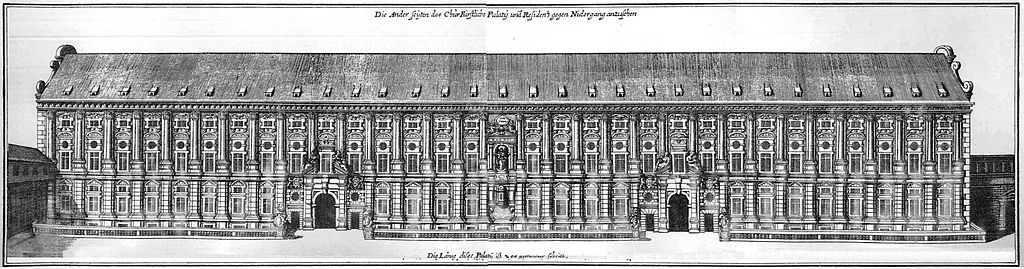

Munich chose to embrace both history and modernization when rebuilding. Many of the city’s most notable historic structures were rebuilt, but unfortunately, the modern reproductions don’t have the same materials and detailing as the original buildings. The images above depict the facades of the Munich Residenz. The left image shows the original building as it appeared during the Baroque Age, and the right shows the modern version.

You can see that all of the depth and sculpture on the facade is now gone, and elements like columns and cornices are simply “drawn-onto” the exterior.

Changes like this were necessary in the post-war rebuilding effort. Although Munich lost much of its original charm & character, the city is still beautiful and impressive today.

Gothic Architecture in Munich

Munich emerged as a leading city in the Holy Roman Empire during the Gothic Age. The city was founded around a former monastery and once contained an assortment of Gothic churches and medieval fortifications. Many of these older structures can still be visited today, and the most notable of these is the city’s main church, the Frauenkirche.

Map of Munich highlighting several works of Gothic Architecture within the city.

1. Frauenkirche

The Frauenkirche is Munich’s principal church and the city’s greatest example of Gothic Architecture. Construction began on the Frauenkirche in 1468 and took just 20 years. The church has a particularly cohesive appearance since it was built in such a short period of time. The Frauenkirche is famous for its two towers, which measure 323 feet (98 m) in height. Both towers are topped with copper domes, which were added to the building in the early 1500s.

The Frauenkirche was built in the heart of Munich on top of a much older church dating from the Romanesque Age. The building contains many of the typical elements found in the Gothic Style. It has pointed arches, Gothic Tracery, and stained glass windows. Remarkably, much of the stained glass at the Frauenkirche survived the bombs of WWII, and now, these windows are some of the best-preserved in all of Germany.

2. Old Town Hall

Munich is also home to a town hall or Rathaus that was designed in the Gothic Style. The Old Town Hall was built in the 1390s, and its tower was once part of the Medieval Walls of Munich. The building is raised one story above street level, allowing pedestrians easy access to the adjacent Marienplatz. For centuries, Munich’s Old Town Hall housed the city’s local government until a New Town Hall was built in the 1800s.

Munich’s Old Town Hall was constructed in three major phases. The first was the original Gothic Phase, which was completed in the late 14th century. Then, during the 19th century, the Old Town Hall was updated with many additional Gothic Revival embellishments. Upgrades like this were common in Germany, thanks to the nation’s embrace of the Revival Movement. The Old Town Hall was completely devasted during the Allied Bombing Raids of WWII. During the reconstruction effort, the building entered its third and present state. It’s similar to the original Gothic Age structure, without the NeoGothic additions.

3. St. Peter‘s Church

Munich originated as a small settlement centered around a Benedictine monastery dating to the 10th century. Eventually, a church known as St. Peter’s was constructed on the site of the original monastery. St. Peter’s Church was built in the Romanesque style in the 12th century and was then rebuilt in the 14th century after a fire. The church has a massive 300-foot (91 m) bell tower that was added in the 17th century. St. Peter’s Church is the oldest church in Munich and one of the city’s most cherished landmarks.

4. Isar Gate

As the capital of Bavaria, Munich was an important military outpost. Like most medieval cities, it had a large fortification system constructed in the 13th & 14th centuries. Munich’s fortified walls contained multiple gates and towers and were a marvel of medieval military architecture. After the walls became obsolete, many of them were torn down to help the city expand. However, certain vestiges, such as the Isar Gate, were spared and can still be visited today.

5. Marienplatz

The Marienplatz has served as Munich’s main gathering place since the 12th century. The space hosts festivals throughout the year and also houses seasonal markets. The center of the square is marked by a Triumphal Column constructed in 1683. It’s known as Mary’s Column and is topped by a gilded statue of the Virgin Mary. The column and its statues are symbols of Munich and are revered by the local population.

6. Sendlinger Tor & Karlstor

Sendlinger Tor & Karlstor are two other surviving remnants of Munich’s Medieval Walls. Both of these gates straddled important trade routes that connected Munich to other cities like Augsburg and Nuremberg. The left image above shows Sendlinger Tor, which still contains its original hexagonal towers from the 1300s. The right image shows the Karlstor. The Karlstor was partially reconstructed over the centuries, but it still shows the influence of Medieval and Gothic Architecture.

Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo Architecture in Munich

Munich’s rulers were some of the first non-italians to embrace Renaissance Architecture. The Wittelsbachs added an Antiquariaum to the Munich Residenz, and St. Michaels Church was also completed in the 1500s. After the Protestant Reformation and the Thirty Years’ War, Munich began to embrace a lot of Baroque Architecture. The House of Wittelsbach commissioned several large palaces and churches throughout the city, which would bring a very grandious character to Munich. The Wittelsbachs were also fond of Rococo Architecture, and they renovated several parts of the Residenz in this newer style.

Map of Munich highlighting several works of Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo Architecture within the city.

Note: #2 and #7 are not depicted.

1. Munich Residenz

The Munich Residenz was the inner-city palace for the ruling family in the Duchy of Bavaria. It was one of two large palaces in Munich, the other being Nymphenburg Palace. The Munich Residenz contains wings designed in the Renaissance and Baroque styles, and several of the interior rooms were updated during the Rococo Age. Unfortunately, large portions of the Munich Residenz were completely destroyed in the Allied Bombing of Munich during WWII, and most of what exists today was rebuilt after the war.

The Munich Residenz originated as a Medieval Castle that was part of the city’s fortification network. However, during the Renaissance, the building was transformed into more of a lavish palace. The image above shows the Hall of Antiquities or Antiquarium. This room was completed in the 1500s and embodies all of the typical elements of Renaissance Architecture. The space is symmetrical and repetitive and has a strong sense of balance and proportion.

This image shows the portrait gallery within the Munich Residenz. The room was designed in the Rococo Style in 1731. Here, you can see a strong contrast to the Renaissance-style portions of the Residenz. This wing contains many typical Rococo design elements, including intricate over-the-top details and lavish materials like gold leaf. The entire Munich Residenz is a great blend of many different styles, and it shows how architectural tastes have changed over the centuries.

2. Nymphenburg Palace

Nymphenburg Palace is the largest of the Royal Residences in Munich. It was built in the mid-1600s during the Baroque Age and also has numerous Rococo additions. Nymphenburg Palace rivals many of the other Baroque Palaces of Europe, including the Palace of Versailles in France and Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. These buildings embody the grandeur and splendor of the Baroque period, when Europe’s wealthy elite competed to have the largest and most lavish possessions.

In addition to a large network of buildings, Nymphenburg Palace also contains an expansive garden. The gardens were completed in 1789 and combine many Baroque and Rococo design elements. The gardens stretch over 500 acres (200 hectares) and are some of the largest and grandest in the entire world. Nymphenburg Palace is located about 4.3 miles (7 km) from the center of Munich and is easily accessible by public transit.

3. St. Michael’s Church

St. Michael’s Church is one of the greatest works of Renaissance Architecture in Munich and the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps. It was completed in the 16th century and designed to mimic the churches found throughout Italian cities like Florence, Rome, and Venice. St. Michael’s is located along Neuhauser Straße, which connects with many of Munich’s major sites like the Marienplatz.

The interior of St. Michael’s Church is particularly striking. The design contains all of the typical elements of the Renaissance Style. There is symmetry and balance, and the space contains many Classical building components like round arches, cornices, domes, and Corinthian Columns. The church’s interior also has a few later Baroque embellishments, which add to the detail and complexity of the building.

4. Asam Church

The Asam Church was built and designed by two brothers as their private chapel. During the mid-18th century, the Asam brothers were well-established artists and craftsmen in Munich. They wanted to build their own church to show off their skills and design abilities. Asam Church is a great example of the many works of Rococo Architecture found in Munich and the rest of Bavaria. The interior and exterior of the church contain all of the typical elements of the Rococo Age, including gold leaf, extravagant details, and dazzling works of Rococo Sculpture.

5. The Church of the Holy Spirit

The Church of the Holy Spirit, or the Heilig-Geist-Kirche, is a Baroque building located in Munich’s city center. Although the original church was completed in the Gothic Age, the main façade and the interior were completely remodeled in the 1700s. The church’s interior is a great example of Late Baroque Architecture and contains bright colors, frilly details, and opulent materials.

6. Theatine Church

The Theatine Church is another impressive work of Baroque Architecture in Munich. It faces the Odeanplatz, and its central dome is a distinct feature in Munich’s skyline. The Theatine church was completed in 1690 and was one of the most influential Baroque buildings in Bavaria at that time. Like so many buildings in Munich, the church was badly damaged during WWII. Much of its facades and interior were redone, and most of what we see today was completed in the 1950s.

7. Amalienburg

The Amalienburg is a small pavilion located in the park surrounding Nymphenburg Palace. The exterior of the building is colored in a pale shade of pink – a common element found in Rococo Architecture. The interior is a complex array of intricate Rococo-style carvings, blended with silver plating and large mirrors. Mirrors were a luxurious good during the 18th century, and many wealthy people installed them within their palaces to impress their guests and show off their fortunes.

8. Hofgarten

Right next to the Residenz, the rulers of Munich built a massive garden known in German as the Hofgarten. The Hofgarten is a great example of Renaissance Landscape Architecture. A highlight of the park is the Dianatempel, a stone gazebo located at its center. Originally, the Hofgarten was only accessible to the Royal Family and their guests, but today, the entire area is a public park.

Neoclassical & Revival Architecture in Munich

The 19th century would bring vast changes to Bavaria and the rest of Germany. The Holy Roman Empire would be disbanded as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, which led to the creation of an independent Bavarian Kingdom. Munich became the leading city within this kingdom, and it was filled with monuments and buildings worthy of a European Capital. The Kingdom of Bavaria would last from 1806 until 1918 and would overlap the Neoclassical and Revival Periods in Architecture. Today, Munich is filled with impressive buildings from this age, particularly in the Königsplatz and along the Ludwigstraße and Maximilianstraße.

Map of Munich highlighting several works of Neoclassical and Revival Architecture within the city.

1. New Town Hall

During the mid-1800s, the local government in Munich had outgrown the Old Town Hall, which had been in use since the Gothic Age. City officials began planning the construction of a much larger New Town Hall, which would be built overlooking the Marienplatz. A Gothic Revival Design was chosen for the building. This was meant to connect with the architecture of the Old Town Hall and the other Gothic buildings in Munich’s city center.

The central tower of the building tops off at 278 feet (85 meters) and features a prominent astronomical clock. The clock is a wonder of 19th-century engineering. It contains a host of statues and figurines that perform a whimsical ceremony each time the clock strikes the hour. Today, New Town Hall still houses the Munich City Council Chambers, as well as offices for the mayor and other city officials.

The New Town Hall contains all of the typical elements of Gothic Revival Architecture. In the image above, you can see pointed arches, gothic tracery, and pinnacles within the facade of the building. Munich has a strong sense of pride in its Medieval History. Neogothic Architecture is a way to mimic the buildings of this long-gone age and reflect on the history and traditions of the city’s past.

2. Königsplatz

Throughout the 19th century, several Neoclassical Buildings were constructed within the Königsplatz – a large square located North of Munich’s city center. The image above shows the Propylaea on the left and the Glyptothek on the right. Both buildings contain all of the typical elements of Neoclassical Architecture, including pediments, statues, niches, friezes, and column capitals from Classical Greek Orders.

This image shows the Munich Glyptothek. The building was designed to resemble an ancient Greek or Roman Temple, with a symmetrical facade composed of white-washed stone. A Glyptothek is a museum that houses statues and sculptures from the Ancient World. There are many famous Glyptotheks in Europe, in cities like Munich and Copenhagen. The Königsplatz also contains several other museums, including the State Collection of Antiquities Museum and the Munich Municipal Gallery.

3. Maximilianeum

The Maximilianeum is an interesting building constructed in the 1850s by Maximilian II of Bavaria. The building sits at the termination point of the Maximilianstraße, a wide boulevard that starts at the Munich Residenz. The Maximilianeum was designed in the Renaissance Revival Style and embodies all of the major themes of the Revival Movement. Today, the building houses the Bavarian State Parliament and has become a symbol of the Bavarian Government.

4. Feldherrnhalle

The Feldherrnhalle is a massive loggia that overlooks the Odeonsplatz. It is located just across from the Theatine Church and is one of Munich’s many Renaissance Revival buildings. The structure was completed in 1841 and designed to be a nearly identical copy of the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence. Just like at the original Renaissance-era Loggia, the Felderrnhalle houses sculptures by notable artists.

5. Maximilianstraße

During the mid-1800s, four large grand boulevards were constructed to connect central Munich with its suburbs. The avenues were named Breinner Straße, Ludwigstraße, Prinzregentstraße, and Maximilianstraße. Of all of them, Maximilianstraße is by far the most impressive. The street begins at the Munich Residenz and stretches in a straight line eastward toward the Isar River. The Maximilianstraße is lined with impressive Revivalist buildings, many designed in the NeoGothic and NeoRenaissance styles.

6. Bavarian State Chancellery

The Bavarian State Chancellery is a modern structure with a unique history. The original building was constructed in the early 1900s and designed in the Renaissance Revival Style. The building was badly damaged in WWII, and during the 1990s, the decision was made to overhaul the entire structure. Today, the stone facade and the dome at the center of the State Chancellery building are the only original elements. The wings on either side are modern additions made from glass curtain walls.

7. National Theatre

The National Theatre is an impressive work of Neoclassical Architecture overlooking the Max-Joseph-Platz in central Munich. The theater was originally built in 1818 but was damaged and rebuilt several times in its history. The current theater was completed in the Great Rebuild of Munich that occurred after WWII. The National Theatre contains many typical Neoclassical characteristics, like a temple-front facade, corinthian columns, and a simple boxy form.

8. Justizpalast

The Justizpalast was completed in 1897 and is Munich’s main courthouse. The building was designed in the Baroque Revival Style and uses many of the same elements found in other Baroque buildings throughout Munich. The facade of the Justizpalast contains many decorative statues and sculptural elements, which give the building a strong sense of grandeur. The Justizpalast sits at the edge of Munich’s historic core, in between the Karlsplatz and Munich Central Station.

9. Siegestor

The Siegestor is a Triumphal Arch and one of the greatest examples of Neoclassical Architecture in Munich. It was completed in 1852 to commemorate the Bavarian Army for all of its successes. The Siegestor was designed in the same manner as the Triumphal Arches of the Ancient Romans. It has three round arches, each separated by a Corinthian Column. The top of the arch is marked by a Bronze Statue symbolizing Bavaria.

10. Bavarian National Museum

The Bavarian National Museum is a large art museum, with galleries focusing on the region’s Medieval Art. Its collections span many of the major movements in European Art History, including Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque. The Bavarian National Museum is housed within a Baroque Revival-style building that was completed in 1900. The building’s design was intended to replicate the architecture of Bavaria’s past, and it is Romanticized with many traditional Bavarian features.

11. Bavaria Statue & The Ruhmeshalle

The Ruhmeshalle is a monument on the outskirts of Munich designed in the style of a Greek Doric Temple. It was completed in 1853, at a time when Neoclassical Architecture was becoming very popular in Munich. The Ruhmeshalle is part of a collection of monuments also containing a bronze sculpture known as the Bavaria Statue. Both monuments overlook the city’s fairgrounds, which house Munich’s annual Oktoberfest.

12. Alte Pinakothek

The Alte Pinakothek is a large art museum located in one of Munich’s greatest examples of Renaissance Revival Architecture. The building was completed in 1836 and was one of the largest and most important art museums of the age. It served as the basis for other major museum expansions in cities like Rome, Paris, and St. Petersburg. Unfortunately, large portions of the original building were destroyed in WWII. The difference in the old & new masonry can clearly be seen in the image above.

13. English Garden

Munich contains a delightful urban park known as the “English Garden” or Englischer Garten. The park was created in 1789 and utilizes the conceptual thinking behind English-style gardens. Unlike French & Italian Gardens, English Gardens attempt to recreate wild and untamed landscapes, with sporadic manmade interventions. Munich’s English Garden stretches over an area of 1.4 square miles (3.7 k2), making it one of the largest urban parks in the world. The garden contains several Neoclassical Pavilions, such as the gazebo in the image above.

14. Karlsplatz

The Karlsplatz is a large circular plaza located next to Munich’s Karlstor. The plaza is located near Munich Central Station, and it is often the main gateway that people cross over when entering the city center. The Karlsplatz is enclosed by a ring of NeoRenaissance facades dating from 1899. The buildings were designed by Gabriel von Seidl, a notable Bavarian architect who also designed the Bavarian National Museum.

15. St. Paul’s Church

St. Paul’s Church is an amazing work of Gothic Revival Architecture in Munich. It was completed in the early 1900s, at a time when Munich was expanding rapidly outside its Medieval core. The population was booming, and several new churches were constructed in order to service the city’s growing needs. The design of St. Paul’s Church was meant to reflect Munich’s proud Gothic history, and it resembles some of the city’s older churches, such as the Frauenkirche.

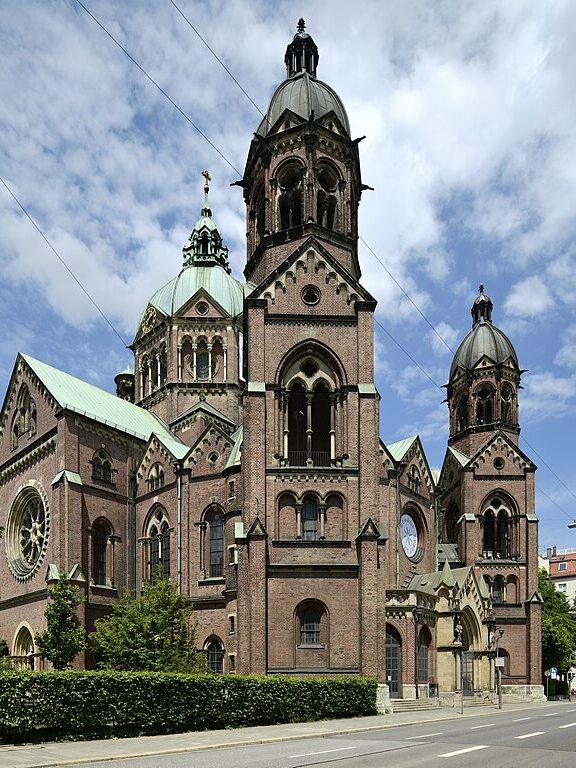

16. St. Luke’s Church

Just like St. Paul’s Church, St. Luke’s Church is another Revivalist building constructed to serve Munich’s growing population. St. Luke’s was designed with a blend of Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival elements. Combining different building styles into one design is often referred to as Eclecticism. Eclecticism was a popular practice during the late 19th century and can be seen in many of Munich’s structures. St. Luke’s Church was completed in 1896, and it sits on the southern end of the city, overlooking the Isar River.

17. Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz

The Staatstheater, or State Theater, is one of many performing arts venues located in Munich. The building was constructed in the mid-19th century and designed in the Neoclassical Style. The Staatstheater still holds frequent performances, including operas, plays, and ballets. The building overlooks the Gärtnerplatz, a circular plaza located on the southern end of Munich’s historic center.

18. Ruffinihaus

The Ruffinihaus is a work of Romanticised Revival Architecture. It was completed in 1905 but designed to appear centuries older. The Ruffinihaus is covered with Medieval-inspired ornamentation common in the Renaissance and Baroque Periods. Today, the Ruffinihaus sits along a prominent pedestrian street in central Munich, and its ground floor is filled with several popular shops. Buildings like this help give Munich its unique blend of traditional and contemporary architecture.

Interested in Revival Architecture? Check out our article on the Architecture of Stockholm to see more great examples of Revival Style Buildings.

Modern Architecture in Munich

In the aftermath of WWII, Munich chose to rebuild much of its historic core exactly as it was before. However, the city still embraced the modern age, and today, Munich is filled with many contemporary roads, buildings, and infrastructure. Munich is home to many of Germany’s largest corporations and has a vibrant finance and tech sector. Munich is among the most livable cities in all of Europe, and it contains a wide variety of innovative contemporary architecture.

Map of Munich highlighting several works of Modern Architecture within the city.

Note: #5 is not depicted.

1. BMW Welt

The BMW Headquarters is a large collection of buildings located about 6 miles (9.5 km) from Munich’s city center. The centerpiece of the whole compound is the BMW Welt, a contemporary building completed in 2007. The BMW Welt is an exhibition space and museum and is a popular tourist attraction in Munich. Visitors can see both vintage and futuristic BMW Cars & Motorcycles. The building was constructed with a massive array of solar panels that generate hundreds of kilowatt-hours of power every year

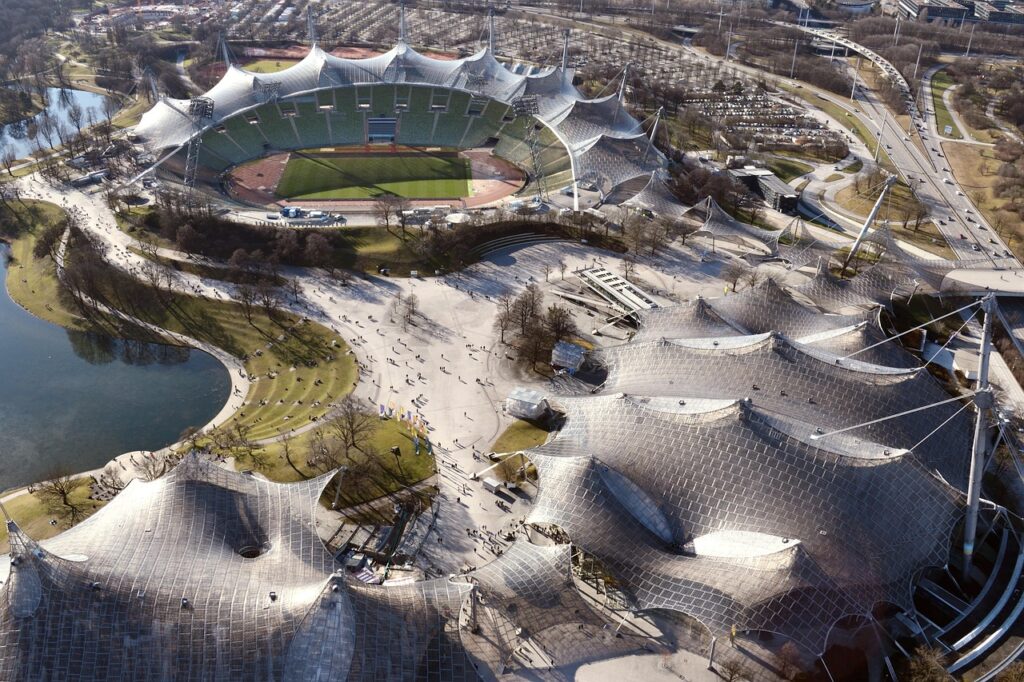

2. Munich Olympic Stadium

In 1972, Munich hosted the Summer Olympics, marking a high point for the city. Günther Behnisch designed a series of pavilions for the event, which today are some of the most recognizable structures in Munich. The pavilions were made from a system of structural members and tension wires that create a large tent-like canopy. This design was revolutionary in the early 1970s and is still replicated today.

3. Ohel Jakob Synagogue & Munich Jewish Museum

In the early 21st century, Munich constructed two buildings that embraced the city’s Jewish History. Both buildings were designed in innovative contemporary styles. The image above shows the Ohel Jakob Synagogue, which was completed in 2006. In the background, you can see the Munich Jewish Museum, completed in 2007. Both structures utilize similar forms and materials, including rough-cut stone and glass.

4. Deutsches Museum

The Deutsches Museum opened in 1925 and is the largest museum in Munich. It sits on an island on the Isar River that’s connected to the city by several bridges. The Deutsches Museum contains a wide assortment of exhibits with a focus on science and technology. The building was designed in the Art Deco Style and features all of the typical characteristics of Art Deco Architecture. It has a strong vertical emphasis, with lots of clean elongated lines and simple details.

5. Allianz Arena

Allianz Arena is currently the city’s largest sporting venue. Construction began on the stadium in 2002, and it was built to hold over 70,000 spectators. The arena is known for its colored lights, which illuminate the exterior. Allianz Arena is located 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) from the city center and hosts football matches, among other events. It’s named after Allianz Bank, a large multinational financial company headquartered in Munich.

Neighborhoods of Munich

Map of Munich showing the extent of various neighborhoods within the city.

1. Old Town

The Old Town is the historic center of Munich. It corresponds with the area once enclosed by the city’s Medieval Walls. The Old Town contains most of the important sites within Munich, like the Residenz and the Frauenkirche.

2. Maxvorstadt

Maxvorstadt is a neighborhood just north of Munich’s city center. This area was largely built up in the 19th century. It contains several works of Neoclassical and Revival Architecture, including the Königsplatz and the Siegestor.

3. Au-Haidhausen

Au-Haidhausen is a neighborhood located across the Isar River from Munich. This neighborhood contains many important government buildings and museums, such as the Bavarian State Parliament and the Deutsches Museum.

4. Ludwigsvorstadt

Ludwigsvorstadt is a neighborhood located just south of Munich’s historic center. Ludwigsvorstadt is more residential than some of Munich’s other neighborhoods. It contains lots of apartment blocks and Munich Central Station.

5. Theresienwiese

The Theresienwiese is a wide open area that is unused for part of the year. However, during late September and early October, the Theresienwiese hosts Munich’s annual Oktoberfest. The celebration focuses on Bavarian beer, culture, and cuisine.

6. English Garden

The English Garden is one of the largest urban parks in all of Europe. It stretches across 1.4 square miles (3.7 K2) of Munich. The English Garden is one of the most visited attractions in the entire city, and it is popular with both locals and tourists.

Architecture of Munich: In Review

Munich has some of the greatest architecture anywhere in Europe. The city has buildings spanning every major architectural age from the Gothic, to the Renaissance, to the Baroque, Rococo, and beyond. Even individual buildings like the Munich Residenz contain varying architectural styles blended together. Munich is regarded as one of Europe’s most livable cities, and it’s home to a thriving economy and a vibrant cultural scene. Visitied by millions each year, Munich is loved for its amazing art, cuisine, culture, and architecture. Whether you go during the Oktoberfest or any other time of year, Munich will surely please any traveler.

- About the Author

- Rob Carney, the founder and lead writer for Architecture of Cities has been studying the history of architecture for over 15 years.

- He is an avid traveler and photographer, and he is passionate about buildings and building history.

- Rob has a B.S. and a Master’s degree in Architecture and has worked as an architect and engineer in the Boston area for 10 years.

Like Architecture of Cities? Sign up for our mailing list to get updates on our latest articles and other information related to Architectural History.